"What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet." - William Shakespeare. Oh, Mr. Shakespeare, how we all love your poetic wisdom. And all these many, many years later, your words still hold so many layers of meaning. Now that's good writing!!

"What's in a name?" I want to consider that question as it relates to writing instruction. Let's look at an example.

I am working right now with a second grade teacher and her class on my graphic narrative unit. This is the 2.0 version of the writing work I did with first graders last year. I am so privileged to have been welcomed into a colleague's second grade class to further my understanding of how young students can access the writing process and produce a narrative product using primarily pictures to tell their stories.

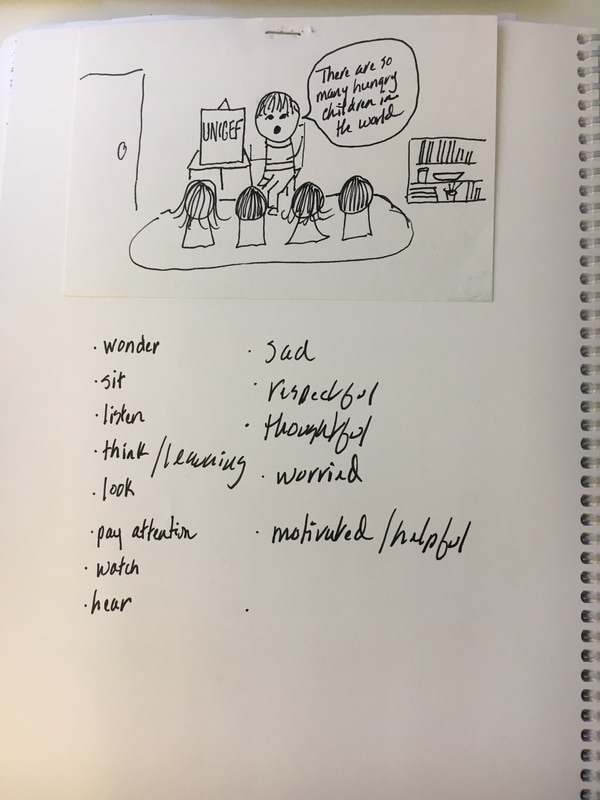

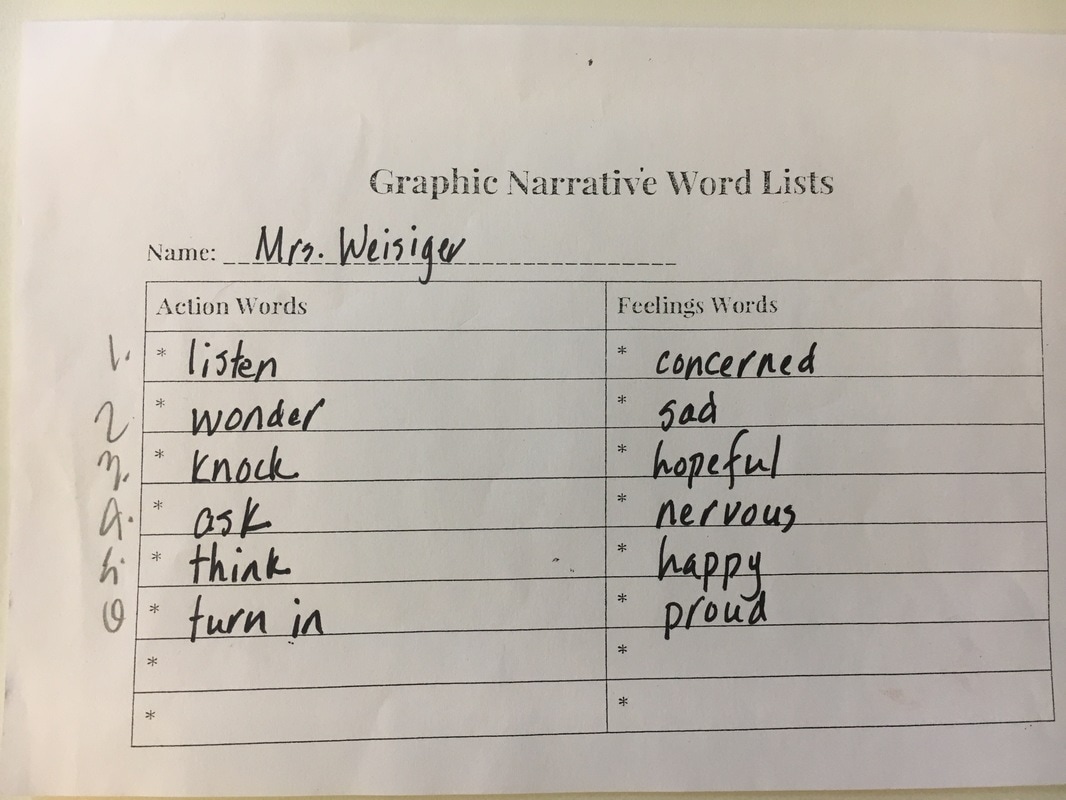

By the end of this week, the students had sketched four introductory seed stories on index cards reflecting their own experiences with solving problems with positive motion. They had each chosen the story they wanted to use for their graphic narrative and created the verb and adjective lists that would anchor their story panels. Finally, (said the students and me!) it was time to create a storyboard of their narratives. The writers laid out their stories across six thumbnails based on the action and feeling words they had already developed.

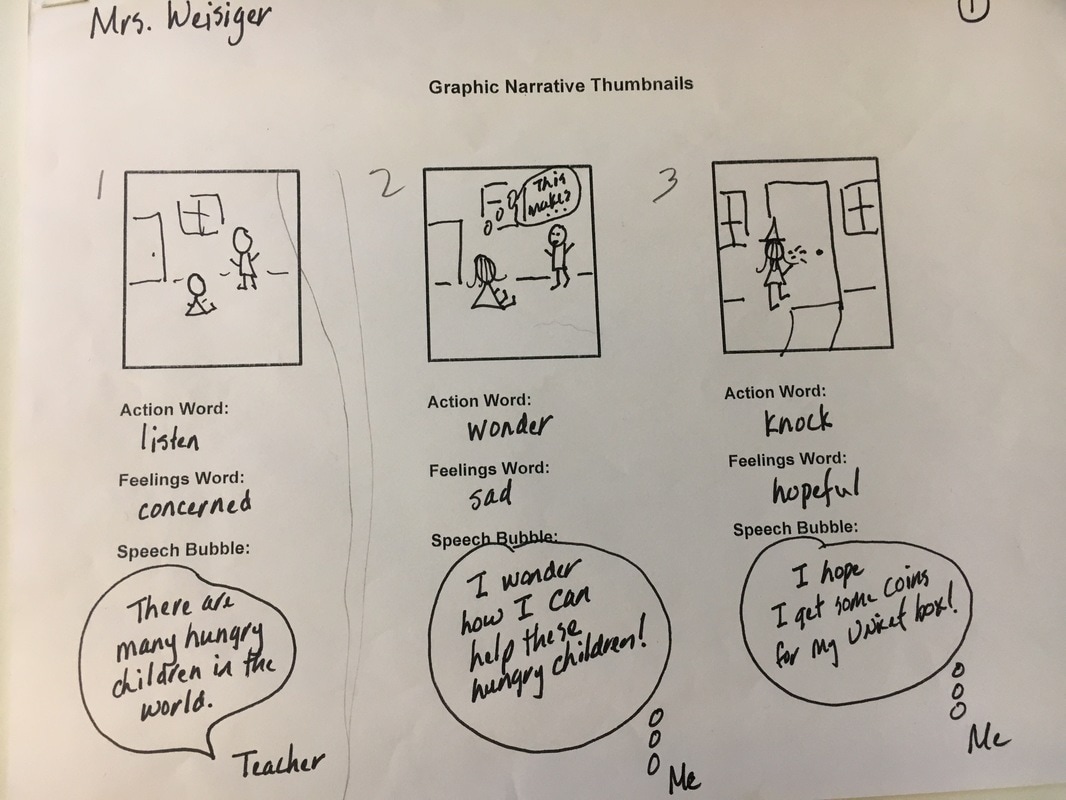

The composition process required the students to draft a six-panel story from the original 3-index card quickwrite (or quicksketch!). Let me show you mine:

"What's in a name?" I want to consider that question as it relates to writing instruction. Let's look at an example.

I am working right now with a second grade teacher and her class on my graphic narrative unit. This is the 2.0 version of the writing work I did with first graders last year. I am so privileged to have been welcomed into a colleague's second grade class to further my understanding of how young students can access the writing process and produce a narrative product using primarily pictures to tell their stories.

By the end of this week, the students had sketched four introductory seed stories on index cards reflecting their own experiences with solving problems with positive motion. They had each chosen the story they wanted to use for their graphic narrative and created the verb and adjective lists that would anchor their story panels. Finally, (said the students and me!) it was time to create a storyboard of their narratives. The writers laid out their stories across six thumbnails based on the action and feeling words they had already developed.

The composition process required the students to draft a six-panel story from the original 3-index card quickwrite (or quicksketch!). Let me show you mine:

And here is where "What's in a name?" becomes a critical teaching question. As the second grade writers were moving their stories from a three-card beginning, middle, and end to a six-panel beginning, middle, and end, some important elaboration had to happen. And, as one student read his story to me from the thumbnails, he realized that he had left out an important part of his story - the motion he took to solve his problem. A critical revision was necessary for his story to be complete.

What's in a name? In this case, some of the most valuable instruction of the unit! When I saw students extending their compositions from 3- to 6-panels (think paragraphs in traditional narrative writing), I named their move! I called it elaboration because I need these writers to understand and internalize the thinking and intentional writing moves they are making so that they can apply them to any future writing. When I noticed the writer recognize that he had left out a part of his story, I called it revision so that he would have the process name for what he had just done with his sketches.

One of the main objectives of this graphic narrative writing unit is for all students to have access to engaging in the writing process and producing a composition that tells an important story about a time in their lives when they saw a problem in the world and solved it using positive motion. Taking them through the writing process, but using pictures instead of sentences and paragraphs, provides a unique opportunity for students to experience the process from an entirely different perspective.

The process is the same, but the product has a different name. It's still a narrative composition; but the pictures tell the story.

What's in a name? When you want student writers to internalize and transfer the thinking that they do as writers, everything is in the name. We need to notice their moves, and name them! Importantly, writing teachers need to be sitting side-by-side in conferences with students in order to notice what they are doing and how they are thinking. Make it a daily practice.

Have a great writing week!

#allkidscanwrite

What's in a name? In this case, some of the most valuable instruction of the unit! When I saw students extending their compositions from 3- to 6-panels (think paragraphs in traditional narrative writing), I named their move! I called it elaboration because I need these writers to understand and internalize the thinking and intentional writing moves they are making so that they can apply them to any future writing. When I noticed the writer recognize that he had left out a part of his story, I called it revision so that he would have the process name for what he had just done with his sketches.

One of the main objectives of this graphic narrative writing unit is for all students to have access to engaging in the writing process and producing a composition that tells an important story about a time in their lives when they saw a problem in the world and solved it using positive motion. Taking them through the writing process, but using pictures instead of sentences and paragraphs, provides a unique opportunity for students to experience the process from an entirely different perspective.

The process is the same, but the product has a different name. It's still a narrative composition; but the pictures tell the story.

What's in a name? When you want student writers to internalize and transfer the thinking that they do as writers, everything is in the name. We need to notice their moves, and name them! Importantly, writing teachers need to be sitting side-by-side in conferences with students in order to notice what they are doing and how they are thinking. Make it a daily practice.

Have a great writing week!

#allkidscanwrite

RSS Feed

RSS Feed